That's not apparent to a visitor who doesn't venture to "the village". Because power follows the highways, an outsider is unlikely to encounter the reality just a few hundred meters beyond the roadway. With the vast majority of Ugandans living in a rural setting, vital public services - schools, health clinics, and churches - are without power. And every evening, most go to bed in darkness or by the dim, sooty glow of a kerosene lamp.

Maternal health is especially impacted by the darkness. Labor pain has no respect for the time of day. When it comes, a mother is in danger if their midwife is unable to see clearly during delivery. This week I had the opportunity to partner with WE CARE Solar to administer the installation of a small solar power kit in the village of Kitswamba, near Kasese in far western Uganda. WE CARE has developed a small, portable and simple solar kit to aid health practitioners save mothers' lives. The idea is to demystify solar and let the user focus on the benefits, rather than the technology. The kit includes a mobile phone charging station, small LED lights, a AA/AAA battery charger, and portable head-lamps. These head-lamps are perhaps the most important part because they provide a large amount of light in a small area, getting the job done without using a lot of energy.

Maternal health is especially impacted by the darkness. Labor pain has no respect for the time of day. When it comes, a mother is in danger if their midwife is unable to see clearly during delivery. This week I had the opportunity to partner with WE CARE Solar to administer the installation of a small solar power kit in the village of Kitswamba, near Kasese in far western Uganda. WE CARE has developed a small, portable and simple solar kit to aid health practitioners save mothers' lives. The idea is to demystify solar and let the user focus on the benefits, rather than the technology. The kit includes a mobile phone charging station, small LED lights, a AA/AAA battery charger, and portable head-lamps. These head-lamps are perhaps the most important part because they provide a large amount of light in a small area, getting the job done without using a lot of energy.Installation

Though WE CARE provided the solar equipment, I asked the Uganda Ministry of Health to contribute to the cost of installation. The purpose was to ensure that the ministry valued what was being provided. I have been pleasantly surprised at their cooperation and enthusiasm for the project. In quick order they approved several hundred dollars worth of funds. The money covers labor and materials such as wire, light-holders, the panel roof stand and nails.

The success of the project depended in large part on the work of the senior administrative doctor, who oversees 25 health clinics in the region. He selected the clinic to receive the kit, convinced the ministry to provide funds, and was instrumental as an advocate. I would not have been able to do it without him.

At the end of the day, the clinic now has a small system to provide a place for mothers to give birth. Success is not guaranteed however due to two on-going issues. The first is cultural: the majority of Ugandan women give birth using traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in their own homes. The ministry is conducting a sensitization program to encourage women to come to health centers for their own safety. That process is ongoing and will take a long time.

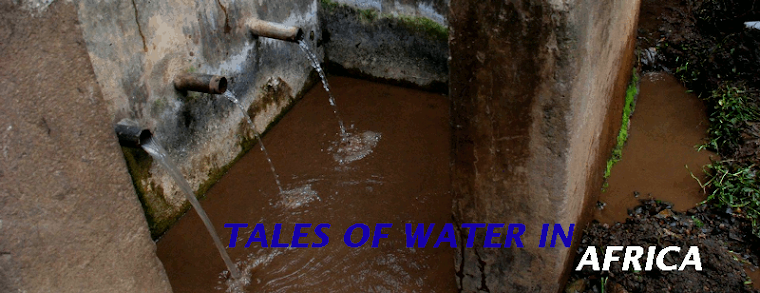

The second issue is water. When I interviewed the on-site doctor, he said in the classic Ugandan way, "we have a problem of water". The clinic has a large rainwater tank, but no connection to a reliable source of water. Without it, performing births becomes much more difficult. I'm not sure how this will affect the Kitswamba health center. Some follow-up will be necessary to judge what has worked, and what is failing.